As an associate professor of political science, Kerry Haynie juggles research and teaching, among other scholarly responsibilities. But as a black faculty member, he feels a burden that his white colleagues do not—the obligation to commit time to sharing his underrepresented perspective.

Duke’s lack of faculty diversity has left some professors of color reporting that they feel overworked. Several black professors have voiced the concern that the cultural perspective they offer can be a double-edged sword, often forcing them to wear many time consuming hats outside of their academic work.

Black faculty members are asked to sit on committees much more frequently than their white counterparts, Haynie noted. For some black faculty, he said, participating feels more like an obligation than a choice.

“Often, many of us do not want to be stretched thin, but we see no way around it because we are not comfortable not having eyes and ears in certain rooms,” Haynie said.

Advisory and administrative committees cover everything from academics to athletics to infrastructure. The University’s Academic Council alone has 41 distinct President or Provost-appointed committees, creating a situation where the same black faculty might be asked repeatedly to participate when white counterparts are not.

"Having too small a pool and constantly drawing from it will make the well run dry," said junior Jamal Edwards, president of the Black Student Alliance.

Ben Reese, vice president for institutional equality, said he could not comment on the feelings of individual professors.

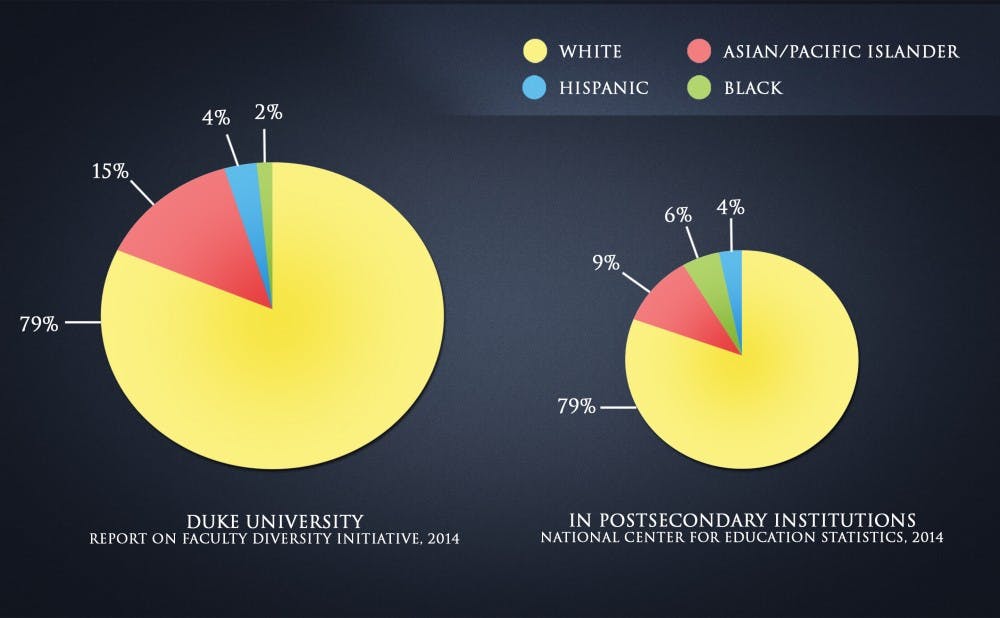

According to the Faculty Diversity Initiative's biannual report in 2013, just 4.2 percent of Duke's faculty identified as black. Other minorities were similarly underrepresented, with 2.1 percent identifying as Hispanic and 14.8 percent identifying as Asian.

Timothy Tyson, a visiting professor of American Christianity at the Divinity school, said based on his experience, he could see how professors of color would say they were overworked. As a white professor, Tyson said, he does not share their burden.

“I don’t feel any obligation to represent white people,”said Tyson, much of whose scholarship deals with questions of race. “Nobody’s feeling any pressure to include more white people on committees.”

Professors of color are often additionally charged with mentoring minority students at predominantly white institutions, said Trina Jones, a professor of law. Although mentoring is a critically important duty, she said, after a while, the hours add up in the “publish or perish” world of academia.

“It takes a toll on your ability to produce. At the end of the day, scholarly production is still hugely important,” she said.

Jones balances her scholarship and mentoring duties with committee work, including her position as co-chair of the Faculty Diversity Task Force. The task force is currently writing a comprehensive review of the state of University faculty. After being established by the Academic Council, the task force has worked to collect demographic information and compare Duke to peer institutions.

The role of faculty mentorship was just one of several roles professors of color are forced to play, Edwards said. He added that with all of their Duke responsibilities, it is easy to forget faculty are people with lives outside of the University.

“They are professors, they are parents, they are husbands, they are wives,” Edwards said.

Professors often feel obliged to speak on important racial issues, he elaborated, pointing to the example of panels held last year following the events in Ferguson, Mo.

Duke’s faculty diversity issues are not unique to the University, Tyson said, noting that he saw a similar situation while a professor at the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Nationally, black faculty are not much better represented than they are at Duke. According to a 2014 report by the National Center for Education Statistics, 6 percent of faculty at degree-granting post-secondary institutions are black.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Edwards said he agreed it is a national issue, adding that this is far from new—and it is not only faculty that feel extra obligations from being at a predominantly white institution.

“Being a black student at a PWI comes with an extra burden. It’s a given,” he said. “We work throughout the four years to create awareness, to raise race relations, to get the university to a more progressive state.”

Haynie said one thing the school could do to address this issue is to do a better job of retaining faculty of color—an admittedly difficult task given the competitive nature of the academic world.

Recruiting black faculty is a difficult task due to a relatively small pipeline, so an emphasis on retention is more effective, Haynie added.

Edwards similarly said the problem is complex and saying Duke needs to do a better job of recruiting overly simplifies the issue.

“Suggesting that would be in ignorance of how difficult it is to recruit,” he said.

“If it were just as easy as that, I think it would be done.”

A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that the Provost convened the Diversity Task Force. The Task Force was established by the Academic Council. The Chronicle regrets the error.